September

September: Bobby’s Favourite Month.

Bertie…….. September has always been Bobby’s favourite month of the year. For many reasons, to be shared with you this September over the next couple of weeks. It is a month of change. Summer drawing to a close. The promise of autumn and winter to come. A time when our wildlife prepares for winter either by staying and adapting or migrating.

The countryside on sunny days in particular can be full of delicious smells of ripening blackberries, and nature’s bounty before it closes for winter. The sun is getting lower in the sky. The mists of autumn are just round the corner. If you are lucky its a time for beautiful sunsets. And sunrises as below on Skomer Island.

People who like writing can see wonder in the words of true wordsmiths. On occasions, you can read an article that really resonates. Takes you back in time or to places, releasing memories so vivid its almost as though you were back there. Such a writer for Bobby has been Michael Parkinson for whom an article on Johnny Haynes, the former Fulham and England footballer, took him back to his young days at Craven Cottage. The home of Fulham FC. That article will be reproduced at a later date.

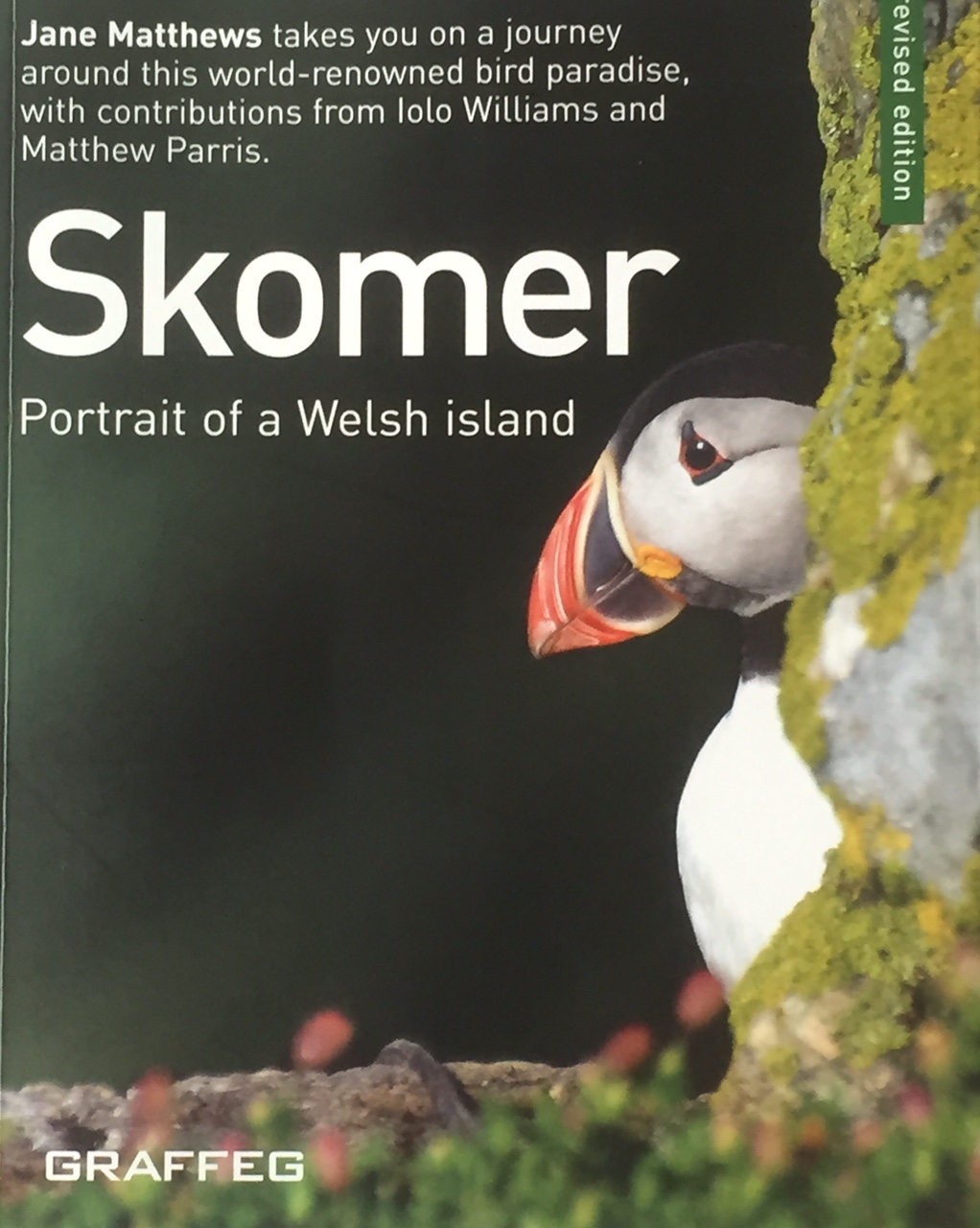

More recently Matthew Parris, the Times columnist, produced an article on Skomer island that made the pulses race. It was reproduced in a book on the island that Bobby was involved with. A book by the warden’s partner Jane, that was based on the photographs of those who loved the island. Be they professional photographers or just volunteers like Bobby. And members of his family. Or Myfanwy who, like Bobby, bought a dozen for her friends and family for the following Christmas! A book treasured on Bobby’s book shelf.

Cover of the book on Skomer.

So, here is the Mathew Parris article. We hope you enjoy it as much as many have who see wonder in the world around us. It is set one night in September. Any September over the last millenniums.

Manx Shearwater.

Matthew Parris.

Flying hopefully into the night, leaving our cares behind.

A PALE HALF MOON was up, which was a pity. Far below we could hear a gentle Atlantic swell licking the rocks. From a cave at the cliff”s feet came the bark of a cow seal guarding her pup. The Pembrokeshire coast glimmered across a strait silvered by moonlight. The slightest of breezes stirred the Bracken.…

The reason it was a pity about the moon was that a fledgling Manx Shearwater prefers pitch black before he ventures out. Until now he has lived almost without light. Below ground in his burrow his parent’s single egg was laid, guarded and incubated. For nearly two months before he hatched, since then he has spent ten weeks growing fat and fluffy in the dark.

His only intimation of a world beyond the burrow has been the rush of wings outside as father or mother fly in – always at night, the darker and stormier the better – with gurgling, cackling shrieks and a delivery of liquid fish paste.

He cannot walk. He cannot fly. Of sun and sunshine he knows nothing, save that on some strange unconscious level in his tiny brain, danger and light are associated, sunlight in which his and his parents’ merciless predator, the Great Black-backed Gull can spot and target a defenceless, feathered fluffball flapping and stumbling in the Skomer Bracken. Even the weak beam of my torch now disconcerts him.

And on that same unconscious level he knows something else, that very soon – perhaps tomorrow – he must fly to Brazil. Tonight he must learn to fly.

Manx Shearwater in Flight.

The Manx Shearwater is one of the wonders of the world… about half of the world’s entire population of this diminished but now stable species breeds on tiny Skomer Island (about a mile wide) and the even tinier island of Skokholm nearby. (See Dream Island blog).

Skomer Island.

Since rats drove shearwaters from the Calf of Man, “Manx” has become a misnomer. Everything about this bird confuses. Sailors mistook the adults night cry – like a demented chicken’s – for the screams of souls in torment. Some fool dubbed the bird a puffin, which it never was, and to this day its Latin name, Puffinus Puffinus, bewilders students, while the French still call it the English Puffin. Until relatively recently its migrations – like its part subterranean lifestyle – have been wrapped in mystery.

No newcomer to the species would guess that the chick – swollen by a diet of oily baby food into a big, fluff upholstered butterball, outweighing its parents – is even related to the slim winged, black and white flying ace of the Atlantic, streaking across the oceans in search of sardines to disgorge into the open beak waiting back in the burrow. Over a life of up to half a century one bird may fly further than to the moon and back.

Manx Shearwater Chick.

I am learning such things. With me on Skomer to help to teach was the permanent warden stationed there by the Wildlife Trust of South and West Wales, Juan Brown. We tied up at the jetty after lunch. Juan directed us to the ruins of an old farm… There are no roads or cars and we walked a grassy track through rocks and Bracken, carrying sleeping bags… and food. A few gulls patrolled. Rabbits gambolled. All was quiet and sunny. Nothing – nothing except the honeycomb of burrows everywhere you looked, and the occasional heap of feathers around a gull – pecked fledgling corpse – alerted the rambler to a parallel universe beneath our boots. Inches underground lay a nursery city, the Rome of the shearwater world. Tens of thousands of hearts were beating down there, hundreds of thousands of small hopefuls, new – feathered, were awaiting their big moment. Their big moment was soon.

At dusk my producer walked the half mile across to the warden’s cottage. Juan Brown knew his stuff and sounded keen, though he must have heard the questions a thousand times. I asked how fledglings know September is the time to come out of their burrows by night and learn to fly?

Their parents simply leave, he said. They fly off to South America. They just have. A few days later the chicks scramble from their burrows. Nobody is sure why.

How, I asked, do these young birds know the way to South America? Nobody’s sure of that either. Some think the birds brain responds to the Earth’s magnetic field, but the great ornithologist Ronald Lockley, who lived and worked on nearby Skokholm more than 60 years ago, proved that shearwaters orient themselves best when the sky (night or day) is clear. He had two shearwaters crated up and sent to Boston in America. They arrived back in their Skokholm burrows – their exact burrows – before the letter advising of their release.

How, he asked, did they do this?

The Moon from Skomer.

Here’s the moon from Skomer. The milky way is a bit more difficult and the shearwaters do not like a night like this.

Go into the night on a starry night. (No moon). There is only one place on Earth from which at (say) midnight on Tuesday 16 September a clear sky at night will appear as it does from where you’re standing – and that is where you now are. If you always knew the date and time, and if you could access a complete set of star maps for every time and place, then you could locate yourself by selecting the map which matched the sky you see. This, it is thought, is what migrating birds do.

But this navigational system must be pegged to a point of reference: the burrow from which the bird first emerges – and to which, after six years feeding and maturing – he will return to breed. So, stumbling and staring around outside his front door, he is locking onto the sky. For the rest of his life all flight paths from and to this point, this starry map above one tiny hole in the surface of one tiny island in one tiny corner of the great Atlantic Ocean.

“Follow me,” said Juan Brown . “Now its dark, and we’ll walk up to the very best area for burrows.”

Something had happened to the footpath we had walked down at twilight. It was littered with baby shearwaters. You would at first have thought these birds were dying – sick, perhaps, or poisoned. Each was flopping desperately around. They could not stand; when they tried walking they would fall forward onto their breasts. Their legs were too far back to balance so they kept toppling, beak-in-the-dust.

“Having their legs set back” said Juan, “is the perfect design for pursuing fish underwater.”

The truly wonderful Manx Shearwater.

We reached the top of the knoll. I tried switching off our torch. It took time for my eyes to adjust to the dark. When they did, the sight was amazing. It was as if the undergrowth had come alive with pigeon sized birds , two-tone, black-and-white fledglings. A few still had patches of butterball down but most had lost it.

Spreading out their wings – long, black, slim, curved and beautiful – they try to balance. Some were crawling up rocks, cheeping, beating their wings to give them lift, clawing with webbed feet at the rock, teetering on the top, then taking off for exploratory flights which always ended in a painful and undignified crash into the bracken.

“But they’ll learn fast,” said Juan, as one more advanced than his peers whirred a full 20 yards down the hill, then came a cropper.

Two chicks were necking affectionately. For all those months underground each may have thought himself the only chick in the world, alone but for the parental beak with its fish paste meal.

“They mate for life,” said Juan.

Everywhere you looked, dark shapes floundered around. On every rock a teetering chick clambered for possession and a launch pad. The whole island, to every horizon, was alive with them. We stood and wondered for an hour.

“You should have been here before the parents left” said Juan. “The noise is amazing.”

Bertie interjects: – “Play this video. Loud!”

Manx Shearwater in full flight.

He explained that on arrival from South America the breeding pairs float just offshore in great rafts of birds, waiting until nightfall. Then, under the cover of darkness they dive straight in, each for precisely the nest from which they came.

When the egg is laid the parents take it in turns to incubate, and later to fetch food. But they come in only at night – the darker and stormier the better – shrieking to their chick, from whom they always seem to be able to identify from the thousands of others.

Returning to our cabin around midnight I slept peacefully but awoke in the small hours and, hearing flapping, walked out into the dark.

All the stars were out. The Milky Way was clear and strong.

I stood there alone for a long time. Apart from the apprentice flyers clawing, crashing and flip – flopping in every direction. I was alone below a vast sky. A cold breeze hinted at an approaching autumn. As I stood a young shearwater lurched over my foot – then began to climb my leg, his wings beating. To him I suppose I was just another rock.

What did he know of the journey which lay ahead? He may still be on his travels when mine are over.

I felt as I stood there a solitary and privileged witness to a supremely important moment in the life not only of individuals but of a species. Beneath the canopy of the stars, something immense and timeless was stirring.

xxxxxxOOOOOOOOOOxxxxxx

Bertie – Thank you Matthew. This is an astounding story that is taking place this week in Wales. Not so far away in our own country. There are all sorts of dangers. The wildlife charities in West Wales are geared for shearwater emergencies. A storm can drive them off course and they can land in town centres well away from the sea. Even on the island a bad storm can disorientate them. One morning, Bobby and the other volunteers found some hiding close to their quarters and collected them and put them safely back underground. It was an incredible moment for Bobby to have this small creature in his hands knowing what it was capable of.

Bobby and the Chick.

Goodnight Skomer.

To see shearwaters flying:

For more information on visiting or staying on the islands:

www.welshwildlife.org/skomer-skokholm.

Recommended viewing:

www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-wales-37295334

Lighting a Candle for Diddley.

Today, we are in my favourite London church. St Martin in the Fields. Most Tuesdays I am in London and head here. Light a candle and then down to the crypt for apple crumble and custard.

St Martin’s is renowned for its music of course. Indeed, the dramatic music for the entrance of the funeral was recorded here. Handel’s “Arrival of the Queen of Sheba”, conducted by Sir Neville Marriner. Diddley and I had many musical times here. We loved the Crypt café.

Just remember, if you go to a concert, to take a cushion or hire one for a £1. Hard pews. On occasions, you can hear the odd siren outside but, in general, you leave the tourists and the razzmatazz of Trafalgar Square behind and enter a building quite different to many London churches. Peaceful and in a way homely, with its abundance of wooden pews and balconies. Here’s Kyla May lighting her own candle to granny last week.

Kyla May, lighting a candle for Diddley.

It’s a brilliant book Bob. Thanks for sharing