Swift’s Hill. A Nostalgic Return.

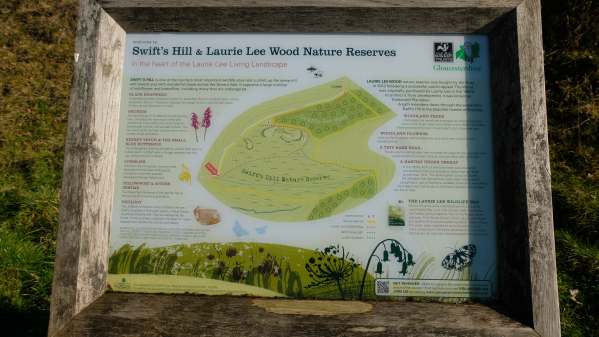

Swift’s Hill

The panoramic view. Slad, Gloucestershire. Looking towards Stroud, the Severn estuary and the mountains of Wales beyond.

Each year, in February, we make a nostalgic return to the Cotswolds around Stroud.

The Friends of the Islands of Skomer and Skokholm always have their reunion at Bishops Cleeve, near Cheltenham, in Mid February. This year’s was on 16 February.

We come to re-enact our commitment to Diddley’s ashes on 15 February, by climbing to the very spot we released them in 2016 on Swift’s Hill.

We come to see Slimbridge where they got engaged on 15 February 1999. We come to see the wonderful snowdrops. We come to see old friends.

Last year we wrote “Cotswold Reverie“. This year we listened to a Radio programme describing a new book on Laurie Lee. Not the words of a wordsmith, but the recorded transcript of a day when a Television producer walked and listened to the poet reminiscing in and around the Slad Valley. The recordings came to light recently and have been turned into a little book. We introduced you to that little book “Down in the Valley” in the story about Laurie Lee’s memories of his old chum Frank Mansell last week.

We saw that programme years ago and would love to see it again. The recordings were made in 1994. Laurie Lee died in 1997. We didn’t know Diddley then and saw the programme repeated years later on Channel 4. It was called “Laurie Lee’s Gloucestershire – A Writer’s Landscape”. Just a small part of those interviews is recorded here.

Swift’s Hill

(as remembered by Laurie Lee in 1994)

“I’m sitting at the foot of Swift’s Hill. It seems to command the whole of the valley from Stroud up to Bull’s Cross. Swift’s Hill just stands here like a great ancestral hump. There are quarries here, partly limestone quarries, partly the old ragstone quarries. The old quarry man in Elcombe, I remember him well in a corner in the woods, he’d come to the quarries in the morning, he’d take out the stone and he built all the walls going down to Stroud. He was the last of the dry stone wall quarry men and this lovely old yellow stone comes from these quarries.

Swift’s Hill

Close up of the interpretation board in the above picture.

Cotswold dry stone wall.

And behind me is Slad, my little village in the valley itself, it’s one of a family of valleys. There’s Sheepscombe, Painswick, Bisley, Chalford. They all have a kind of family likeness; same feel, same light, same trees, same families.

I think, sometimes, I was brought up here, I was born here and I’m still living here, and I feel I know every detail of all this countryside around. And it’s not only the trees and the stones and the houses, it’s the people. They are equally endemic, they are rooted to this part. They are just as rooted to these parts, as are the stones and the quarries and they have these family names like Swain, Partridge, Hogg, Webb, West, Lee, White, Fuller. A number of the names belong to the wool trade. Fuller for instance, Webb, Spinner. So when I think of this place, it’s not only for its undying, rapturous beauty, it turns slowly to the seasons and becomes a different person, equally beautiful, from spring to winter. But the people are the same. They are rooted. They are the valley, they are the Cotswolds. They don’t move and they teach me their irreplaceability and I’ve learned that I don’t move either. I come back and here I stay.

14 February 2020. Looking down on Slad, from Swift’s Hill. February 15 was given over to Storm Dennis.

I’ve long wanted to know how to describe this part. I’ve long wished to discover a way of describing this part and the sensation of living here and associating the valley with the people and with its community and with its history; its pre-Roman, its pre-Bronze Age, its Stone Age history, and I suppose in a way it’s been my life trying to filter through, in a simple a way as possible, a communication, a description, a condensation, a concentration of simple language, which can convey to others, not necessarily living in these parts, but living in other parts of Britain, what it’s like to live here and what it’s like to maintain this ancestral life. And a sense that I have of witnessing a moment in time which is reflected from the trees, from the quarried stone from the walls, from the houses, from the bleating animals who pass. The bleating sheep, which you hear in the background, who are passing on their ancestral fates, from one season to another.

I was sitting the other night in my garden, listening to the sheep, and I hope they’ll forgive my saying so but it’s the only time I’ve heard a sheep, a ewe, bleating with any kind of authority. Generally speaking they’re wimps but when they have lambs in the spring they suddenly take on a different kind of voice. Which the Hoggs do and the Webbs do when they grow and marry, they take on this same kind of authority, and I think the animals and the birds and the people do reflect the uniqueness of this valley. The blackbirds in my garden and the blackbirds in the garden at the end of the lane, they go off to Africa, as I did when I went round the world once as a young man, but they always come back here, they come back to the same garden, to the same tree, the same wall, the same nest and they imitate their ancestral voices, and no wonder they sing with a Gloucestershire accent, because that’s how they were raised.

When I went to London for the first time people used to say;

‘Why do you talk in that extraordinary American accent?’ ‘That’s not American, that’s Gloucestershire. We sailed from Bristol, we sailed from Plymouth, we were a West Country accent.’

‘Oh is that? I thought you were Irish!'”

Slad, with Swift’s Hill in the background.

These are green pods of valleys, they have a family shape. If you were dropped down into one of these valleys, you would not know which one you were in because they are so alike in their verdant greens. They’re like pods. I was trying to describe it once to friends who didn’t know this part, and I said that living in our valley was like being broad beans in a pod, so snug and enclosed and protective. And these valleys are just like that, they have this protective, miniature closeness, which in some ways explains why a lot of people still living in the village have never been to London, never even been to Swindon.

I tried to describe this valley through the seasons and how it changed, its personality changed, so that in spring and summer and autumn and winter it was a different place, a different country almost and we boys, as kids, we were all ready to change our own attitude, our own games. It was either skating or it was snowballing or it was climbing trees, scragging apples. Whatever was true to that particular season was something we were ready to adapt ourselves to.

I remember walking through the village one very hard winter’s morning, the dogs going by wrapped in the vapour of their own breath and the boys not knowing quite what to do, they wrapped themselves in moist scarves, choking and pink faced. One said. ‘What we goin’ do then, eh?’ Nobody knew what they were going to do and someone was flapping their arms and then another one, suddenly he took off and he began to whip himself with a stick.. ‘Get up then’. He’d found something to do and then we all got up and we all whipped ourselves with sticks and we all galloped through the town like Genghis Khan; like the words from Tartar. And that was our game. The game slipped into this sense of winter. We galloped round the corner and down to the farm and the we galloped down to the pond, skimming across the ice and looking down at the bubbles and lilies waiting for summer to release them. I could never skate but all the idiots in the village seemed to be able to skate on one foot. They’d go sliding and gliding by and I’d always fall on my face and I thought, those drummondry louts, once you put them on ice they become Nureyev, they become star ballet dancers. Winter brought out that star quality.

But then in summer, summer was a time for playing the moon and the whole of the valley became our playground, and we’d run and run. We had a game called fox and hounds, and some of the lads would start off, we’d give them perhaps five or ten minutes and then we’d follow them. Starting in the village and running up through the valley galloping up through the valley, galloping up through the woods. You were allowed to shout one thing: ‘Whistle or holla or we shall not follow’. And they had to answer or we didn’t know where they were. ‘Whistle or holla or we shall not follow’. And then you’d hear, right up the valley, some little disguised call showing where they were and we’d go after them. Those sort of games and the moon, running with the mad hares on the top of the hill.

And I’ve tried to remember and have often remembered the quality of those moonlit nights, which had a quality of such unmoving and immortal stillness and excitement, with a full moon hanging above Swift’s Hill. Rising tides in one’s brain of Slad and summer, which linger there even now. That was summer. Chaps going up through the street, saying to the ladies, ‘hot enough for yer then?’. To be answered with a worn-out shriek. Dogs lying under rain-butts, to get out of the heat. And we boys lying in the grass, listening to the loops of cuckoos going across the valley and not knowing what to do, having nothing to do. No ideas in our heads. Nothing moved except summer. This radiant luxury of stillness. There was nothing to do but summer.

Well having laid down and done nothing because there was nothing to do, summer, someone would say, ‘Well let’s go down the pond then’. So we’d get up and go down the pond, and halfway down there was a little village shop on the corner by the old Elizabethan house, the big house, where, we’d buy some sherbet dabs. That is what I remember as being an element of a summer’s day, to buy sherbet dabs with a liquorice tube in it. If you sucked it was alright but if you blew, the bag exploded and you choked in a sort of paroxysm of sherbet and people coughing all over the road.

Coming out of school, haymaking. We’d rush off to the farms and say, ‘Can we help?’ Anything to get out into the fields after a long day of timetables, I mean tables. And the going off, helping the men forking sheaves onto the wagons and then getting waylaid. It wasn’t as deliberate as all that. We didn’t go over there to be seduced, we went over there to be a man and to help the men with the haymaking. But there was always, well not always, a Rosie type in the grass, waiting to waylay one of we sturdy lads. That was their job. Temptresses. Temptresses of summer, and this one stopped me. I wasn’t looking for trouble but I got it. She said:

‘I got somat to show ye then.’

I said, ‘You ain’t.’

‘I have. Come here.’

So I stuck my fork into the ringing ground and followed her like doom and we went down onto a wagon where there lay a large stone jar. ‘It’s cider, you ain’t to drink though, not much of it at any rate.’ So we unstopped it and I held it to my mouth. Never to be forgotten, that first long drink of golden fire. Wine of wild orchids. And of that valley and of that time and of Rosie’s burning cheeks. Never to be forgotten or ever tasted again.

That’s what haymaking meant to me, and that’s what cider meant to me. That’s why it got me into trouble. But it wasn’t haymaking. The step, the first half step, towards willing, half willing seduction and it taught me a lesson, that women are stronger than men. The valley was education, the valley taught us everything, we didn’t have to go anywhere.

Then when I was seventeen I left the valley. But leaving is a thing that is normal with the young. They leave the home as they grow. The cottage is like a nest. They grow and they fill it and there are too many of them and then they go off to see the world, make their fortune. They have to do that. I think it is an instinctual movement, to go out, leave home and see the world, and then possibly send money orders back to your mum. When you’ve made it.

And I went off one summer’s morning and walked. I’d never seen the sea so I walked south to Southampton, then along the south coast and up into London and worked on a building site. I remember somebody saying, when anybody leaves home they always end up working on a building site, well I did. Then when that job was over I went to Spain for a year, with my violin. And that was one of the most carefree, happiest times of my life, discovering this almost medieval Spain which in many ways reminded me of home. It was all horse traffic in Spain, horses and mules, and I was leaving a village which was all horses and my mule and chaps sitting round and gossiping at night, and that sort of community which I’d left still existed. So it was a natural thing to do I think. I went to about forty countries while I was away: the Middle East, Africa and to Mexico. But I knew that I would have to come back here.

As a child I used to think that all the world was like this valley. This is the world. Born and the eyes open, you immediately register what you see, and I register this uniquely beautiful valley and I thought this is life, everything’s like this. And I didn’t realise until I’d gone to all these other countries that nothing is like this. When I came back I thought, no I don’t want to go again, I’m here, I’m rooted, I’m back.

The graveyard is opposite the Woolpack. I have been fortunate to survive this long and to survive very difficult crises abroad but I’ve got back and now it’s all wrapped up. I drink in the pub and when I go, I will go across the road, or I’ll be taken in a box and put in the churchyard. And it’s the comfort of peas in a mood again. I’m wrapped in this little pod which is my home.

The Woolpack with Swift’s Hill behind (mostly behind the tree!).

I’ve found a place halfway up the churchyard, which is near enough to the church to be aware of, in the spiritual sense, to be conscious of matins, Sunday morning, but also to be within reach of, in a temporal way, orgies on Saturday nights in The Woolpack. And alternating between the temporal and the spiritual is the way I wish to spend what eternity is left to me.”

Slad church, with Laurie’s grave just to the right as the path bears right.

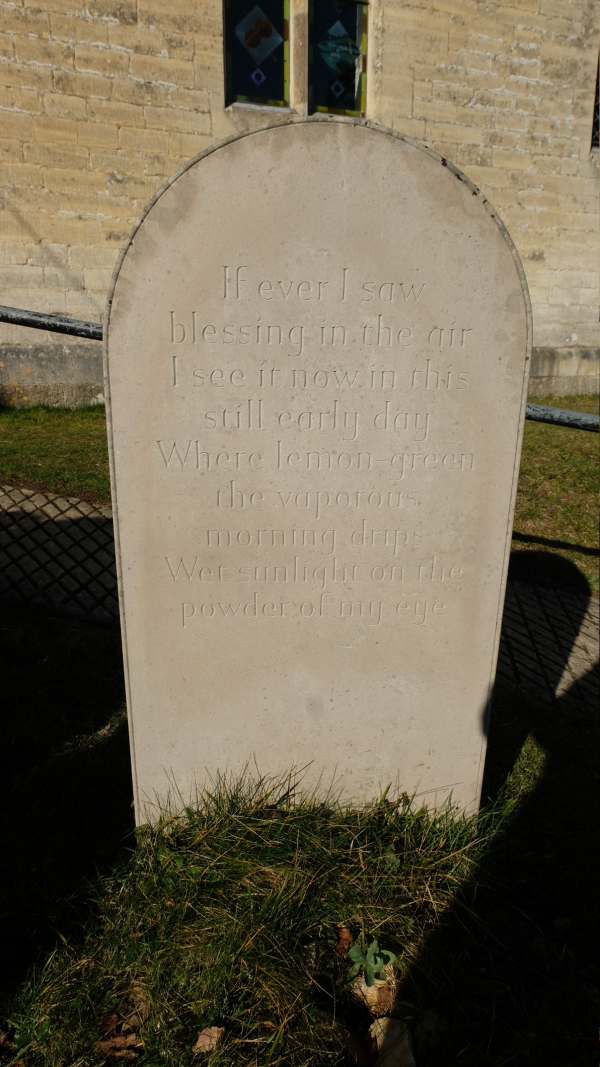

Laurie Lee’s tombstone. 1914-1997.

If ever I saw

blessing in the air

I see it now in this

still early day

Where lemon green

the vaporous

morning drips

Wet sunlight on the

powder of me eye

————

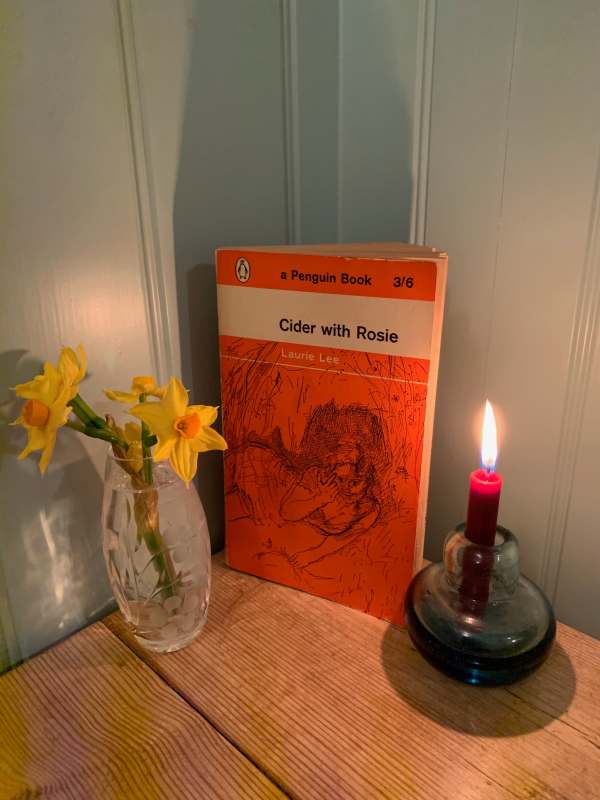

If you would like to watch an excellent documentary on Cider with Rosie, Joanna Trollope included the book in the series “The Secret Life of Books”. Here it is:

Cider with Rosie

Laurie Lee in Slad, perhaps at the time he wrote Cider with Rosie, first published in 1959.

Lighting a Candle for Diddley

Bobby: “I first read Cider with Rosie when as a schoolboy I borrowed it from my local library. Probably about twelve years old, living in a nice bit of suburbia, it was a million miles from the utopia described in the book. A utopia with its fair share of menace. I was captivated and still am. Every few years I feel drawn to reading it again and the experience is just the same. Describing a place that was so far away in distance and understanding I could only dream about. Until I met Diddley. She took me to Slad. Showed me her first school and walked with me up Swift’s Hill. It was a dream come true. And now I return every year to undertake the same rituals.

One sad fact about Cider with Rosie is that it was chosen for the school curriculums. Not just here, but in America as well. In doing so, it alienated a generation by treating it as something to be dissected for schoolwork. One such was our Technical Director, Tim.”

Tim: “To be honest, this was over 45 years ago. I wasn’t into reading much at the time – other than Melody Maker and I was probably still reading the Beano too! But, it wasn’t my kind of story in the first place. I already hated English Literature as a subject. I simply couldn’t care less why the author used one word in preference to another. I thought then (as I still do now), it was probably his favourite word for the situation. Nothing more, nothing less. To be force-fed a book that I wasn’t inclined to read in the first place – and to then study it to a depth that the poor unsuspecting author never intended in the first place was simply an anathema to me. A totally pointless exercise. This book was consigned to the same pit as Gerald Durrell’s ‘My Family and other Animals’. Maybe I should try and read these books again as some sort of healing process. The way Bertie tells us that Bob waxes so lyrical about it almost encourages me to do so. But the damage runs deep.”

– – – – – – – – –

Leave a Reply